A road to remember

The Great Ocean Road is one of Australia’s most scenic drives. Winding its way along 243 kilometres of Victoria’s rugged south-west coast, it attracts millions of visitors each year.

But what many do not realise is that the road was built as a permanent memorial to those who died during the First World War.

Carved from wild and windswept cliffs overlooking the Southern Ocean, the Great Ocean road was built by 3,000 returned servicemen fresh from the trenches of the Western Front in memory of their fallen comrades.

“It was just an idea that was floated by a couple of men,” said Dr Meleah Hampton, an historian at the Australian War Memorial.

“They had long wanted a road to connect all of these coastal towns in southern Victoria so they floated it as an idea for using the manpower of these returned servicemen, and then they decided: ‘If we are going to do it, let’s make it a memorial.’

“It was a huge endeavour.”

At the time of the First World War, the remote south-west coast of Victoria was accessible only by sea or rough tracks through dense bush.

“The whole focus has been on sending men away to fight, and suddenly we’ve got 350,000 men overseas,” Dr Hampton said.

“That’s an entire workforce, and as time goes by it dawns on people that these men are going to have to integrate back into society.

“What are they going to do with them? How are they going to avoid civil unrest? How are they going to avoid having dissatisfied men roaming the streets? And how are they going to avoid all sorts of other social problems?

“So people start turning their thoughts to how they are going to manage this and the Great Ocean Road is born out of that situation of fear and worry about what civil Australian society is going to look like after the war.”

The chairman of the Country Roads Board in Victoria, William Calder, proposed the repatriation and re-employment of returned soldiers working on roads in sparsely populated areas in the Western District.

“The men who are coming home are just a little bit worried too, and the AIF immediately puts in place things like education programs, and there are discussions about what their options will be,” Dr Hampton said.

“We all know about the solider settlement scheme and how it is not necessarily a success, but it is a sign of the need at the time and one of the different ways in which people are trying to solve this problem.

“And the Great Ocean Road is in itself a private endeavour to help solve the same problem.”

Calder submitted a plan for what he described as the 'South Coast Road', starting at Barwon Heads, near Geelong, following the coast around Cape Otway, and ending near Warrnambool.

“At that point in time some of the worst battles are yet to come,” Dr Hampton said.

“As they are putting forward the idea of a road, Australians are launching the battle of Amiens.

“So in the same month that they are working on this idea for all these men coming home, there are fewer men to come home, and the idea of the road becoming a memorial becomes this real hand-in- hand process.”

It was Geelong mayor Alderman Howard Hitchcock who brought the plans to fruition and first saw its potential as a tourist attraction for the region.

He formed the Great Ocean Road Trust and set about raising the money to finance the project.

He saw it not only as a way of employing returned soldiers, but of creating a lasting monument to those who had died during the war.

“The Australian Corps suffers thousands of casualties up until the 5th of October so the process of designing and planning to build this road happens while there are hundreds of names appearing in the newspaper,” Dr Hampton said.

“There’s news of Victorian kids who enlist in 1914 and survive the entire war, who were going to come home and build this road for them. And they’re now in the paper as having been killed, so it’s a really fraught time.”

The Great Ocean Road Trust managed to secure £81,000 in capital from private subscription and borrowing, with Hitchcock himself contributing £3,000. Money would be repaid by charging drivers a toll until the debt was cleared, and the road would then be gifted to the state, connecting isolated settlements on the coast and becoming a vital transport link for the timber industry and tourism.

Survey work began in August 1918, but the difficult terrain, dense wilderness and bad weather hampered the project.

Construction work officially began in September 1919, but progress was slow with workers achieving around three kilometres a month.

“Sometimes there are hundreds of men working on it, and sometimes there are just 10 or 20,” Dr Hampton said.

For their efforts, the returned soldiers were paid ten shillings and sixpence per day – significantly more than the six shillings they received in the Army, making the project a popular one.

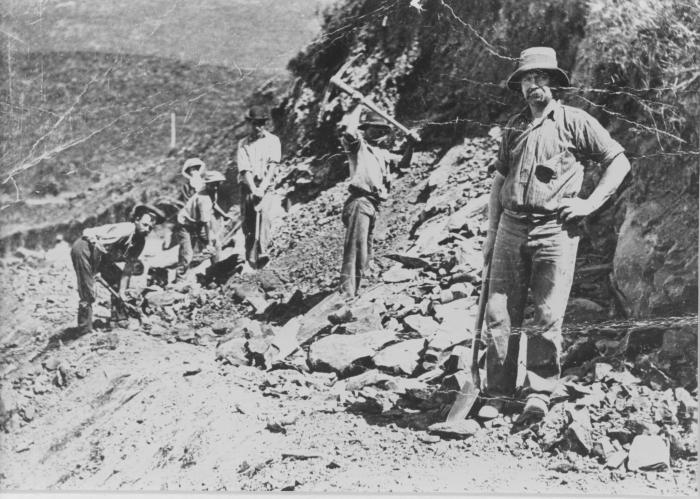

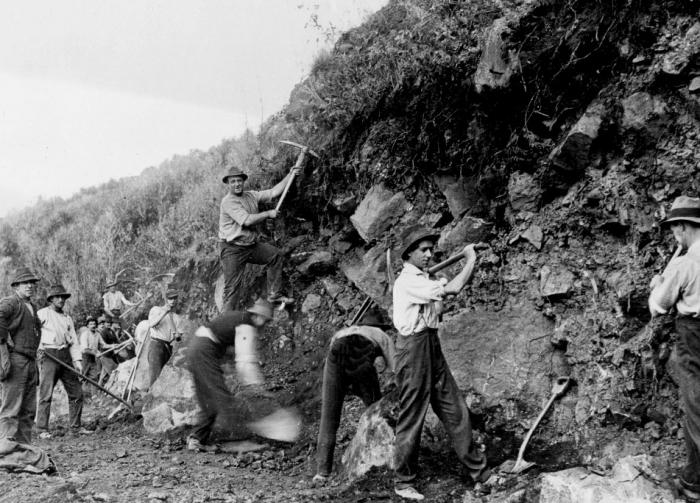

Through rugged terrain, wild weather and steep rocky cliffs, the soldiers worked for eight hours per day, and slept ‘rough’ in the bush, sleeping out in old army tents in tent cities that moved along with the road.

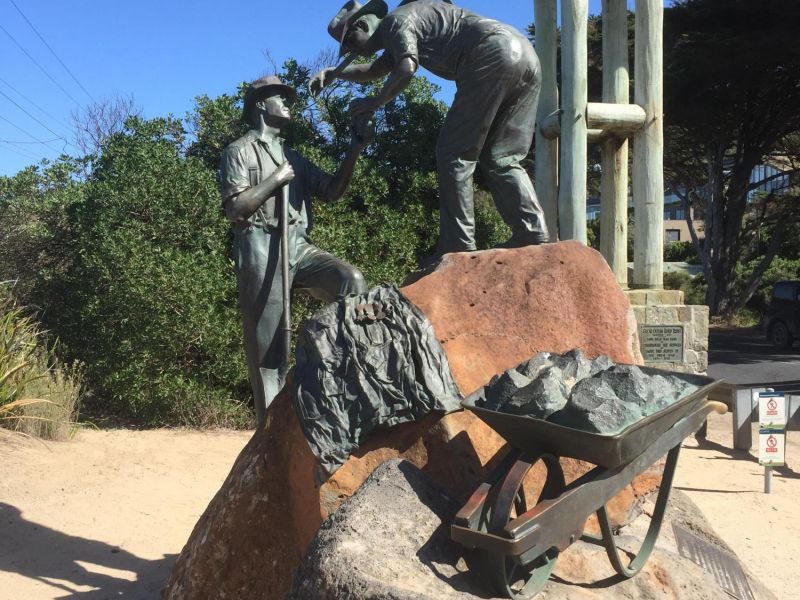

Construction was done by hand using picks and shovels as well as explosives, wheelbarrows, and horse-drawn carts.

The work was at times extremely dangerous, with numerous workers killed on the job; the final sections along the steep coastal mountains being the most difficult to work on.

“It was pretty awful,” Dr Hampton said. “The survey team would go in ahead to survey the next bit of the road to be built, and the men who were building it would come in behind them.

“There are even stories of the men going forward in carts with explosive detonators on their laps so that they wouldn’t jiggle around too much on the road.”

On 18 March 1922, the first section of the road, from Eastern View (where the ANZAC soldier sculpture can be viewed today) to Lorne, was officially opened with due pomp and ceremony.

It would be another ten years before the section from Lorne to Apollo Bay was finished, officially marking its completion. The road was officially opened in November 1932 with Victoria’s Lieutenant-Governor Sir William Irvine holding a ceremony near Lorne’s Grand Pacific Hotel.

At the time, The Age newspaper reported that: “In the face of almost insurmountable odds, the Great Ocean Road has materialised from a dream or ‘wild-cat scheme’, as many dubbed it, into concrete reality.”

It was at this time the road was dubbed the world’s largest war memorial.

“The Geelong mayor, Howard Hitchcock, was a really important driver of the whole project,” Dr Hampton said. “But he died just before it was opened.”

Hitchcock died of heart disease on 22 August 1932, though his car was driven behind the governor's in the procession along the road during the opening ceremony.

A memorial was constructed in his name on the road at Mount Defiance, near Lorne, and he is still affectionately considered the Father of the Road.

Not long after the opening a toll was put in place to recoup construction costs for the road. Visitors were charged two shillings for cars, and 10 shillings for wagons with more than two horses, payable as they passed through Eastern View where a memorial arch was erected.

The toll was abolished when the trust handed the road over as a gift to the State Government in 1936, with the deed for the road presented to the Victorian Premier at a ceremony at the Cathedral Rock toll gate.

“It was a really dangerous road for quite a long time,” Dr Hampton said. “There weren’t a lot of places to turn out, passing was really difficult, and it was often a one car road, but that’s because it was built by men with picks and shovels on the edge of cliffs overlooking the sea.”

In 1962, the road was deemed by the Tourist Development Authority to be one of the world’s great scenic roads, and in 2011, the road was added to the Australian National Heritage List.

“It was a really big deal,” Dr Hampton said. “They managed to put together 30 odd cars for the opening, and in 1932 nobody had cars, so that was a big deal in itself. They’d thought about it for ages, and now they were doing the thing that they wished they could have, and their parents had wished they could have, so there was a lot of hope too. They felt useful and they were really excited to have it; they wanted people to know, ‘This is our memorial.’”

19 September 2019 marks 100 years from the day construction commenced on the Great Ocean Road. During September and October the Centenary is being remembered with a range of activities including a new documentary 'The Story of the Road', Augmented Reality and an Art Trail.

Visit https://www.visitgreatoceanroad.org.au/iam100/ to find out more.