The Callaghan Brothers

The Callaghan brothers were born to Mary and James Callaghan of Lithgow, New South Wales.

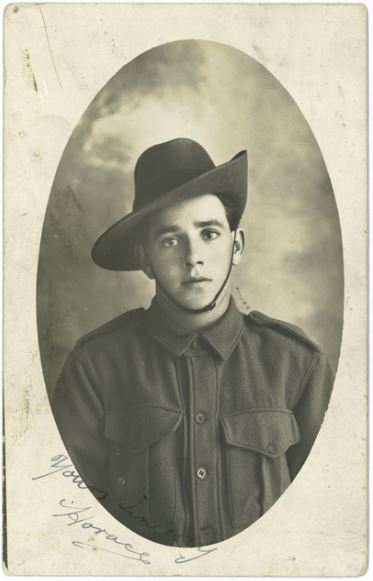

Walter was born in 1888, Stanley in 1894, and Horace in 1898. All three attended Lithgow Public School.

Walter went on to work as a drop forger and munitions maker at a local small arms factory, while Stanley and Horace worked in the nearby coal mines.

For many young men, the outbreak of the First World War represented an opportunity for adventure that could previously only have been dreamed of. Horace, the youngest of the three brothers, was desperate to sign up. He first attempted to enlist into the Australian Imperial Force in his local town of Lithgow, but local authorities rejected his application because he was only 17 years old. Undaunted, he journeyed north to Queensland, and in August 1915 he lied about his age, eventually joining the reinforcements of the 9th Australian Infantry Battalion.

Stanley enlisted not long after in October 1915; Walter in July 1916, by which point he had married Essie Pearl Chadwick, and had a daughter child, Vera Catherine Callaghan.

After a brief period of training, Horace embarked from Brisbane in January 1916 for the adventure he so desperately wanted to join. He was too late to participate in the campaign on Gallipoli, but instead went to Egypt, where he Australian Imperial Force was in a period of growth and reorganisation. In March 1916 he left Egypt with the 9th Battalion, and less than two months later, was in the trenches of the Western Front

Horace’s first major battle on the Western Front would also be his last. The 9th Battalion moved to the front line on the 19th of July, tasked with holding a sector of the trenches near the town of Pozières. On the 21st of July, they commenced an attack on German positions. In bright moonlight they assaulted the German trench, but were pushed back in heavy fighting. They then received orders that they were to form part of the 1st Australian Division’s attack on the town of Pozières itself.

Horace took part in the first attack soon after midnight on the 23rd of July. He ran across no-man’s-land in the darkness, but when he was about 100 metres from his trench a series of German flares lit up the battlefield. Horace jumped for a nearby shell crater to hide from view, but died instantly from a gunshot wound as he tried to reach cover. He was 18 years old. In the confusion of the battle that followed, his body was lost, and his name is now commemorated on the Australian National Memorial at Villers-Bretonneux, along with over 10,000 Australian servicemen of the First World War who have no known grave.

Stanley Callaghan received news of the death of his brother just weeks before he arrived in France. Allotted to the 18th Infantry Battalion, which was serving in the Ypres sector of Belgium, Stanley was immediately faced with the horrors and hardships of trench warfare. On the day of his arrival, his unit came under German high explosive artillery fire.

Stanley and the 18th Battalion trained and rested behind the lines, and moved to the Somme region of northern France where the men were forced to endure the seemingly endless rain of October and November, and the mud and cold that came with it. They could not stand still in one place for very long because if they did they would sink down to their knees in the muddy quagmire. Many were hospitalised with trench foot and hypothermia.

Stanley experienced the hardships of trench warfare, but also spent time training at a trench mortar school, where his excellent conduct was noted by his superiors. On the 15th of November, not long after he had rejoined his unit after mortar training, Stanley’s unit was camped behind the lines when an errant German shell landed amongst them. Stanley was killed instantly. He was 22 years old

Today, his remains lie buried in the Longueval Road Cemetery in France, with over 200 soldiers who died in the First World War.

Walter Callaghan served in the 54th Battalion, which he joined in the Somme region of France in January 1917. Exposed to the elements and German artillery fire, the hardships and horror of trench warfare took their toll. In April 1917 Walter was hospitalised with “pyrexia of uncertain origin”. While the exact nature of his illness is unknown, this term was often used to describe men suffering symptoms of post traumatic stress disorder, or “shell shock”, as it was known.

Rejoining his unit in June, in the following months, Walter and the 54th Battalion moved north to the Ypres region of Belgium. His first major battle came on the 26th of November when he participated in the battle of Polygon Wood. Australian troops successfully took their objectives and held off German counter attacks, but suffered over 5,700 casualties in a single day.

In late November Walter was again hospitalised, this time with “trench fever”, an illness usually caused by lice, which were present in large numbers due to the difficult and unsanitary conditions that troops were forced to endure.

His traumatic experience of war was made harder by the knowledge that his two younger brothers, Horace and Stanley, had already been killed. Recognising her husband’s trauma and the tragedy faced by the Callaghan family, in late January 1918 Walter’s wife wrote to the authorities pleading for him to be allowed to come home. He was having fits and rapidly losing weight. She pleaded: “I feel very worried about him. He lost two brothers in 1916 one in July and one in November: so I really think his mother has done her share for her country and there is no more that can go”. Despite her pleas, Walter Callaghan continued to serve at the front.

On the 13th of April 1918, after having moved back south to the Somme region, Walter and his unit came under heavy German artillery fire as they were in the process of being relieved from front line duties. Walter was hospitalised with shrapnel wounds to his left hand, an injury that was so severe that he was sent to England to recover.

He rejoined his unit in late August 1918, but his return to the front was to be brief. On the 1st of September, months before the end of the war, Walter was wounded in action during the assault on Mont St. Quentin. He and his unit jumped out of their trenches at 5 am into a heavy German bombardment. Walter was badly gassed, and received severe gunshot wounds to the head. Everything was done to try and save him, but he passed away in hospital on the 4th of September.

His remains now lie in the St Sever Cemetery Extension in France, along with over 8,000 Commonwealth soldiers who died in the First World War.

He was 31 years old. Survived by his wife and young daughter, and the third of three brothers to die in the war, the loss of the Callaghans had a huge impact on their home town of Lithgow. In October 1918, their mother was honoured by opening the Lithgow Soldiers’ Memorial, a small gesture by the town to acknowledge the sacrifice of her sons.