'It's more than just a name'

If there’s a war memorial near you, then Henry Moulds wants to know about it. A volunteer guide at the Australian Memorial in Canberra, he has been fascinated by memorials since he was a child.

“I’ve been collecting photos of war memorials for years,” he said.

“My interest began when I was little with my dad. He was a Second World War veteran, and we would go to Anzac Days and things like that.

“I remember going to the memorials and seeing the lists of names and my dad explaining why his name wasn’t on a particular memorial. I became really interested in how communities commemorate and how we remember.”

Over the years, Henry has taken thousands of photographs of memorials in towns and cities around the country.

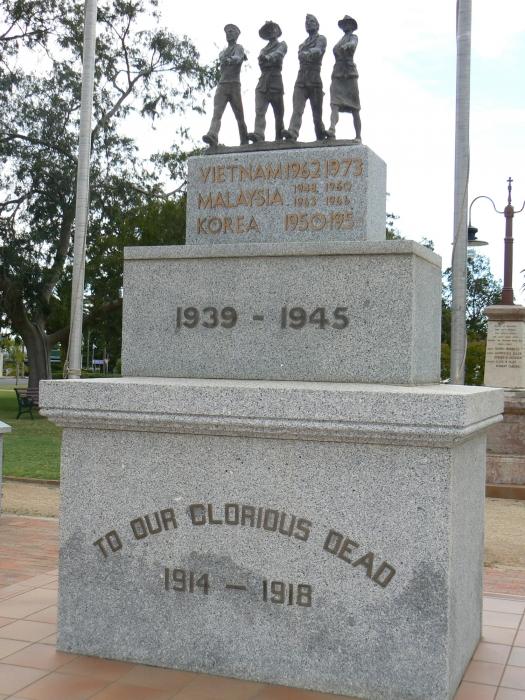

These memorials now feature on Places of Pride, the National Register of War Memorials, which aims to record the locations and images of every memorial in Australia, from cenotaphs, honour boards and church shrines to memorial halls, pools, bowling clubs and tree-lined remembrance ways.

Launched just before Remembrance Day 2018 to mark the 100th anniversary of the end of the First World War, the Places of Pride website now features more than 10,000 war memorials.

Henry has contributed more than 400 new memorials to the website since it first began, and has added stories and photographs to hundreds more. Now a volunteer working on the project, he encourages others to do the same.

“There’s a huge range of memorials, and it’s that variety that really intrigued me,” Henry said.

“We went from small things like a seat with a plaque right up to the Australian War Memorial.

“And then there are the memorials where the town no longer exists. A good example is Millie near Narrabri in New South Wales. It’s a Boer War Memorial, but it’s just in a paddock now, and there’s no town around it anymore.

“Being able to research the stories behind them, and find out what I can about the people so that people can see it’s not just a name, it’s not just a big chunk of granite or sandstone is what I love.”

He tells the story of the Wall brothers from Wangaratta in north-east Victoria. The three brothers all joined together during the First World War, and all served on Gallipoli together and survived. They all went on to the Western Front, and all died within three days of each other.

“It’s these amazing stories that bring home what these memorials are all about, and I’d love to see more members of the public being able to contribute, not just photos of the memorials, but the stories behind the individuals,” Henry said.

“Whenever I have the opportunity to travel, I keep my eyes open,” he said.

“You’ll just be travelling down a backroad somewhere and you’ll see what looks like a memorial. It might be to pioneers, or immigrants, but every now and then it will be a war memorial, and then I’ve got to find out what it is, and where it came from.”

Ranging from modest memorial plaques and honour rolls to grand museums and monuments, war memorials were often erected in prominent civic areas such as town squares, parks and gardens, or central avenues and intersections to mark Australia’s participation in the First World War and commemorate those who had died.

They took on a multitude of forms, ranging from cenotaphs and obelisks to statues and pillars. Ornamental structures, such as windows, flagpoles, gates or arches, were also popular, as were memorial buildings, such as halls, schools and pools, and remembrance drives and building projects such as the Great Ocean Road in Victoria.

“Tambar Springs in NSW is another good example; it’s a classical figure of a soldier leaning over his rifle … but the story is that it was created by a local farmer, and the face is said to be the face of his son who was killed in action.

“It’s a really poignant memorial, and it’s the stories behind the people that bring them to life.

“You look at some of the memorials from these small communities and you see the same surnames.

“Particularly in the First World War, they were brothers, or even fathers and sons, and then you see the number with a little cross or a symbol next to them, and you realise a lot of those young men didn’t come back …

“Then you look at the Second World War, and it’s the same surnames, just different initials, but there are also the ones where the initials are the same, and you think, are they men who have served in two world wars?”

Today, these memorials continue to be an important focus for Anzac Day and Remembrance Day ceremonies around the country.

For Henry, who devoted a lifetime of service to his country — serving in the army and navy as well as the Australian Federal Police — they are particularly poignant.

“Having stood catafalque party around some of these memorials on Anzac Days and Remembrance Days reminds me of what service to our country is all about,” he said.

“One of the really rewarding things to see today is the acknowledgement of not just the First World War and the Second World War, but the more recent campaigns, right up to the most recent peacekeeping operations, and Afghanistan.

“Communities are not forgetting, and I think that’s the really important thing. That’s why I love Places of Pride. It’s reminding people that these memorials are not just things of the past. They are an acknowledgement of the men and women who are serving our country today, and I think that’s really important for us to keep in mind; they are a living testament to service.”

As a voluntary guide at the Australian War Memorial, Henry is passionate about the Memorial and about sharing the stories of Australia’s servicemen and servicewomen. He has travelled thousands of kilometres around the country to photograph memorials, and plans to continue for a long time yet.

“I love it, I really do,” he said. “I love sharing this place with people, but I love sharing what it means as well.

“I first came here to the Australian War Memorial with my dad back in the ’60s as an eight or nine year old, and I used to come here all the time.

“Whenever I had free time I would come here and just spend some time wandering around … even if it was just half an hour to go to a new part or spend a bit of extra time in a particular gallery …

“That’s the thing with the Memorial, it’s constantly evolving … We’ve got the galleries now that cover the most recent conflicts, but I think we need to tell more of those stories because they are the people who are coming through the galleries now. They are bringing their kids; they are bringing their grandkids; and I think it’s good to be able to tell their stories as well as the stories of the First World War diggers and the Second World War.

“And that’s what I like about Places of Pride: it reminds people that some of these conflicts are mentioned. Forbes is a good example. I had photos of the big cenotaph. It had 1914–1918 and 1939–45, so that’s the two world wars commemorated, and when we went there last time, it’s got East Timor and Iraq and Solomon islands. They’ve updated it, and they’re saying this service is as valid as any other service, and that’s what I like to show people. We are still committing ourselves to a world where Australia is involved in peacekeeping and in military operations, so we have to acknowledge what those people are doing.

“I think it’s important for people to know that their communities, and their individual memorials, are all part of a national commemoration, and I want to encourage communities to contribute to Places of Pride because it’s about community contribution and to remind people that your great uncle’s story is just as important as every other story.”