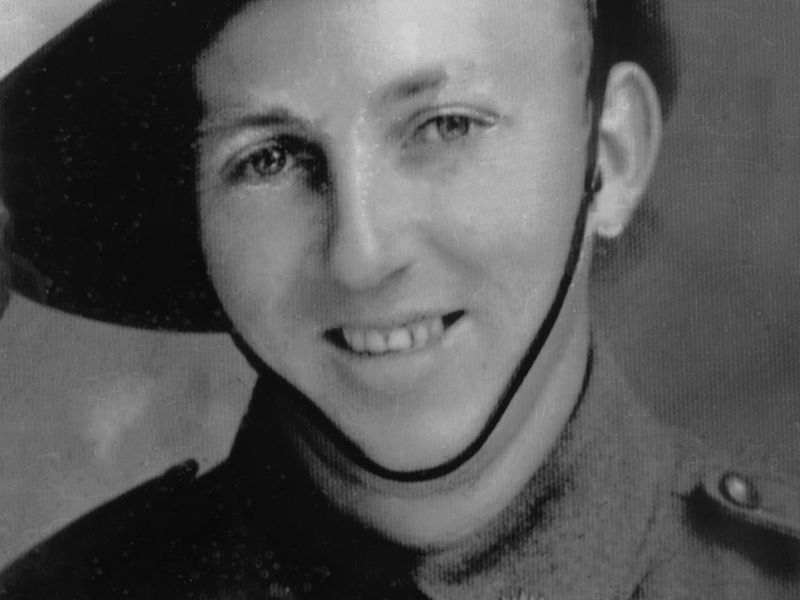

William (Bill) Neville Walker

Bill was born on the 25th of January 1914 at Jingellic, NSW. He was one of seven children of William and Louise Matilda (née Kohn) Walker. On the 13th of April 1935 he married Katherine Mary Neil. In August of that year, their first child, Terrance was born at Corryong. Tragically, Terrance would die one month later, on the 22nd of September. Later they would also have a daughter. During the 1930’s and into the early 1940s William was a motor driver in the Jingellic area.

Bill enlisted at Royal Park, Victoria, on the 20th of August 1941. He was allotted the Army Number VX63237 and taken on strength with the Australian Army Ordnance Corps. He was transferred from Royal Park to Bendigo where he completed the rest of his training to become a Group 2 Motor Transport Mechanic. Early in the new year Bill was posted to the 2nd/10th Ordnance Workshops, also based at Bendigo.

Bill and his unit embarked aboard the transport “MV” at Sydney on the 10th of January 1942, disembarking at Singapore about two weeks later. Even as the troops were disembarking the Island of Singapore was suffering from major air attacks by the Japanese. It’s not known what role the 2/10th Ordnance Workshops, and therefore Bill, played in the defence of the island but five days after the unit disembarked all British Empire forces had withdrawn from the Malay Peninsula onto Singapore Island. At 2030 hours on the 15th of February British and Commonwealth Forces surrendered. More than 100,000 troops became prisoners of war and Bill was one of them. His fighting war had lasted less than three weeks. Initially, Bill would have been taken to Changi Gaol along with all other POWs.

Bill would have eventually found himself moved sometime around July of 1944 to the River valley Road Transit Camp, as it was here that POWs bound for Japan aboard the Rakuyo Maru were housed. It’s not known whether previous to this he worked on the Burma-Thailand Railway or remained in Changi. It wasn’t until the 3rd of September 1944 that it was announced the ship was ready for boarding.

Bill was among 2218 prisoners of war who were marched down to the docks at Singapore. Before them were two old ships flying the Rising Sun but no markings to indicate that they would be transporting prisoners of war. The POWs were made to sit on the docks in the full sun, while coolies loaded the two ships with rubber and tin. 900 British prisoners were loaded onto the Kachidoki Maru while all of the Australians, 718, and the remaining 600 British were loaded onto the Rakuyo Maru. As Bill walked up the gangplank he was handed a 2ft by 2ft block of rubber with a handle to carry on board. Every POW that passed into the ship was given one of these. Korean guards armed with sharpened bamboo sticks forced the men into the cargo holds. The Japanese realised that not all of the POW’s would fit below decks, so they allowed half of them to stay up on deck.

The ships pulled away from the docks and anchored midstream. They would remain here in the dark, crowded and stiflingly hot conditions for 36 hours before finally getting under way and forming up on convoy along with two other cargo ships, two tankers and four naval escorts.

Six days into the journey, at 0155 hours on the 12th of September the escort ship Hirado was struck by a torpedo from the US submarine Growler and sank instantly. As the sun rose over the horizon, the convoy descended into chaos. Torpedoes from a second submarine, the Sealion, struck the Nankai Muru, which was loaded with bauxite and drums of av-gas. At 0531 hours a torpedo struck the the No. 1 hold of the Rakuyo Maru quickly followed by a second that ran into the engine room. The explosion that followed destroyed the engines and generators and caused the ship to list and sink ten feet in the water.

The Japanese on the ship quickly started to abandon ship. They made no effort to assist those POW’s who were stuck below in the holds. 11 lifeboats and 2 small punts were taken by the Japanese as they quickly made an effort to get away from the ship. The POWs that were not below decks began throwing anything overboard that would float. Some jumped overboard and tried to board the lifeboats but were held back by guns and bayonets.

13 hours after being struck by torpedoes, the Rakuyo Maru disappeared beneath the waves. By 1900 the Japanese escorts had picked up everyone they were going to rescue. Floating around in the debris field were approximately 1200 British and Australian POWs.

The story of the sinking of the Rakuyo Maru is far more complex than is described here. It’s not known what Bill was doing or thinking through all this. Although the sea was relatively calm it’s quite probable that he would have been covered in oil and had swallowed a good deal of seawater. Two American submarines, the Sealion and the Pampanito, patrolled the area two days after their attack. They found wreckage but also discovered men who were floating on rafts. As they approached the raft they were unable to decide if they were friend or foe as all of them were completely covered in thick black oil. What followed was an amazing rescue attempt. The Pampanito broke radio silence and asked for assistance in the search and rescue operation. In the following two days the submarines managed to rescue 159 men. Unfortunately Private William Walker was not amongst them.

Bill is remembered on the Australian War Memorial Roll of Honour, the Ballarat Australian Ex-Prisoners of War Memorial, and the Labuan Memorial on the island of Labuan. For his service, he was awarded the 1939-1945 Star, the Pacific Star, the Defence Medal, the War Medal 1939-1945 and the Australian Service Medal 1939-1945.

Stephen Learmonth

Stephen Learmonth