Harold Eslie Ashworth

Harold Elsie Ashworth was born on the 12th of October, 1895, at Allans Flat in Victoria. He was the second youngest of ten children to William and Charlotte Margaret (née Wright) Ashworth. When Harold was only 8 his older sister, Agnes, became ill and died. A brother, Charles, born the year before Harold, also passed away at an early age.

Harold and his siblings were educated at the Staghorn State School No. 1593. After leaving school he helped his father on the family farm at Baranduda. An article in the Wodonga and Towong Sentinel written after his death, described him as being highly respected as an industrious young man.

Harold originally enlisted in July of 1915 but became ill and was admitted to hospital. This led to some confusion and in November, when he was already overseas, a warrant for his arrest for desertion was being conisdered. The authorities discovered that he had reenlisted on the 30th of September. Over the next three years, three of Harold’s brothers would try and enlist, but all three would rejected on medical grounds. Harold was allocated the Regimental Number 1146 and placed on strength with the 6th Reinforcements for the 13th Light Horse Regiment. As he was only 19 at the time, Harold required a letter on consent from his parents to enlist. Within Harold’s service file is a letter written on lined paper with pencil. It states;

“Dear Sir

My son Harold Eslie Ashworth wishes to join the expeditionary forces. It is with our full consent we wish him to join as we feel that every parent must make some sacrifice. Trusting that his going into the ranks may be the means of others joining from this district.”

It is signed by both parents.

Whilst on his final leave he was given a formal send off by the community. It was reported in the 7th of October, 1915, edition of the Yackandandah Times.

"On Monday evening in the school room a farewell social was tendered to two of the recruits, Harold Ashworth and Roy Mason. They are members of the Light Horse on final leave and are expecting to sail in a week’s time. A goodly number of residents turned up to give these lads a final handshake and a keepsake in the form of a wristlet watch. The lads are looking well and the drill has improved them in appearance and physique. One is an inch taller and both have put on weight in camp.”

Harold’s unit sailed for Egypt in October of 1915 on board HMAT Hawkes Bay. Whilst in Egypt he saw service with the 13th Light Horse at Ismalia, Tel-el-Kebir and along the Suez Canal. Later he went to France with the Regiment but applied for a transfer to the 24th Infantry Battalion of the 6th Brigade, 2nd Australian Division, in February of 1918. He followed the battalion through the action at Hamel and volunteered as a stretcher bearer for a period of time.

On the 16th of August, 1918, the 6th Brigade carried out a number of peaceful penetration operations around Herleville, in the north of France. At 0410 hours on the 18yh, C Company of the 24th Battalion advanced to their positions as laid down in the operational orders. The right post, under Lieutenent Rigby, reached the cross roads and commenced to dig in. Unfortunately, between this post and the next on the left was a gap which contained about seventy German troops. These were able to attack the post, inflicting many casualties and taking prisoners, one of whom was Harold.

Harold’s Red Cross Society Wounded and Missing Enquiry Bureau file contains a statement from Private G Hart (5365) describing Harold’s last moments.

“I could not give a description of Casualty as he was in bandages at the time. He was on a German transport on the 18.8.18 with myself going to Tincourt Hospital as a prisoner of war. He was laying alongside of me and he asked me for a drink of water. I told him that he had no water and he got a little delirious and started to throw his arms around. I asked him not to throw his arms about as there was a man next to him with his two eyes shot out. I did not know he was dying but apparently that was his last struggle. He told me that he had nine wounds. The Germans took his boots and socks off and I asked them if he were dead and they replied yes. He was taken off the train at Peronne for burial, and that was the last I saw of him.”

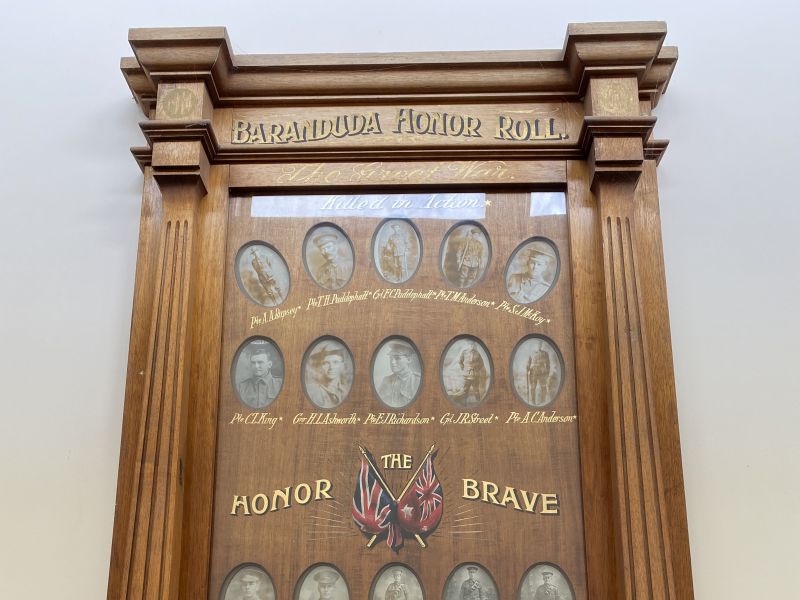

Harold was buried in Plot VI, Row D, Grave 17 at Heath Cemetery, Harbonieres, France. His family constructed a memorial at the Staghorn Flat cemetery. He is also remembered on the Australian War Memorial Roll of Honour, the Baranduda Pictorial Honour Roll, the Yackandandah Holy Trinity Anglican Church and the Staghorn Flat State School Pictorial Honour Roll. For his service during the war he was awarded the 1914-15 Star, the British War Medal, and the Victory Medal.

A friend of Harold’s, Lance-Corporal Allan Grant (967), wrote a letter to Harold’s parents after Harold had died. It was printed in the 15th of November 1918 edition of the Wodonga and Towong Sentinel, four days after war had ended.

“It is with a sad heart that I write these few lines, describing to you how Harold met his death. On the morning of the 18th of August, our Company had been in the line for over four weeks, I had been in the big push from the start to where he stopped. On the 18th we had to advance our posts forward to a depth of five hundred yards on the right of the Company and about 100 yards on the left. On the left it only meant to go forward the required depth and dig a post in No Man’s Land: but, on the right, Fritz’s posts had to be taken and our chaps had to establish themselves in his posts. They were to advance under a barrage which was to play on the posts for a few minutes, but it was too high and missed them, with the result that the machine guns were still speaking when our lads moved off. It was an impossible task with such a few men and those guns in front still firing; but still our lads went on to certain death. Harold was heard say (when someone grumbled) “It is our job and it must be done.” He was shot dead not far from the objective, and as far as I can learn was left there, as it was impossible to recover his body, but our line is sure to be advanced there shortly, and he will then be buried. I was fortunate in being on the left of the Company and we advanced our post during the night, meeting with no opposition. It is a wonder to me that I was not in the raid, for I have been in every ticklish job lately. Of course, I don’t mind in the least for I do as I am told. Words cannot tell how we all miss Harold, for there is not a man or officer in the Company who did not have a good word for him. He was loved and respected by all, and a better soldier and a man never donned a uniform. I do not say this because he was my schoolmate, but I am only voicing the opinion of the whole company.

I know what a great shock it will be to you all to learn that Harold shall never return; but be brave and consol yourselves that he died doing his duty until the last. You know he had been relieved of the stretcher bearing at his own request, as he wanted to do some real fighting. We had been in the line for over four weeks and it was very hard to think that he got knocked on the day that we were being relieved. It is hard for me to write to you concerning Harold, but I feel it must be done.

I am at present proceeding to a bombing school, which is a good way behind the line. To-day [sic] I am in a staging camp in a nice little village, and it is fine to be out of the turmoil and wreckage of battle for a while.”

At the time his letter was published, Lance-Corporal Norman Allan Grant of Staghorn Flat, Victoria, had been dead for over a month. He was killed in action on the 5th October, 1918, at Montbrehain, the last action of the war involving Australian forces.

Stephen Learmonth

Stephen Learmonth