The Forgotten Indigenous Soldiers of Walhallow - Part 3

The Wallaby March

On the 15th of October 1915, at a Narrabri recruiting meeting a march similar to the Coo-ee March was planned, called the Wallaby March, it commenced at Walgett on December 1915. Gamilaroi man, Harold Frazer, was a foundation member of the march. Frazer marched 38 days through Gamilaroi Country and in each town the marchers were greeted with cheering crowds, attended dinners and rallies. Recruitment rallies encouraged young men to join, and every marcher was charged with also being a recruiter, including Frazer. The recruits were given a blue shirt and joined the march to Newcastle.

The Wallaby March may have contributed to the unusually high number of enlistees for Gamilaroi men in 1916, if not joining the march, then enlisting soon after. The Wallabies formed the basis of the locally raised 33rd New England’s Own and 34th ‘Maitland’s Own’ Battalions.

Interestingly, Harold Frazer’s military record tells an affirmative story, while not forgetting he was one of the few men that survived to serve the duration of the war. Once in England Frazer, was sent to the Lyndhurst Bombing School, promoted to corporal, and graduated as an instructor. He was sent to the Western Front and was injured inaction on the 5th of April 1918. Returned to London for treatment, he remained in hospital care for the remainder of the year. Within this time, he met and married Dorothy Eliza Wilson of London. They married on the 7th of November at St Simon’s Church in Paddington in the presence of Dorothy’s father. With the permission of the A.I.F, Frazer brought his new wife to Australia in July 1919.

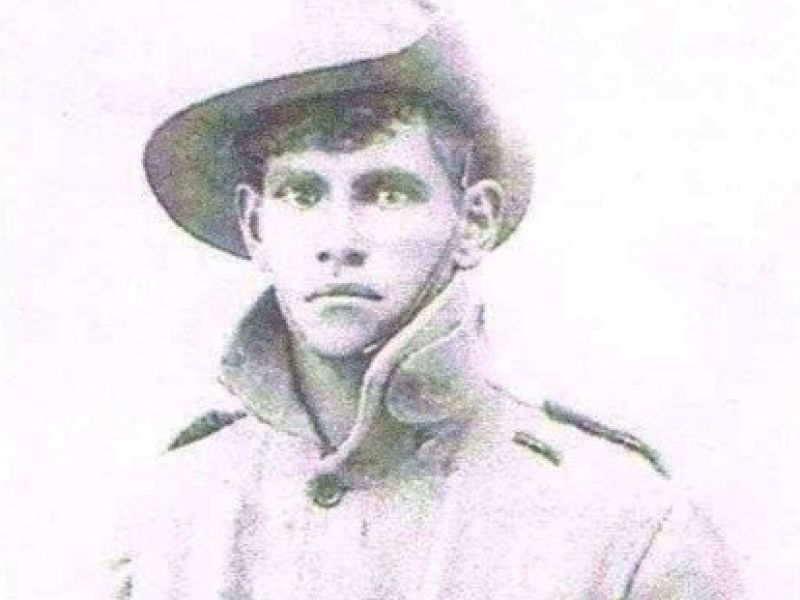

Walhallow’s Vincent Watley joined the march in Gunnedah on the 14th of December. He was eighteen years old and he was only five foot three inches high. He joined with twenty-two other young men from Gunnedah that day. As they marched through the town ‘aglow with flags and bunting’ a spectator shouted: “your feet will be sore before you reach Sydney, matey”. A blue shirted recruit fired back, “Yes, me boy but it’s not cold feet we’ll be having.”

As the Sydney Morning Herald reporter remarked ‘a more heterogeneous lot of men would be hard to find’.

Vincent was killed in action on the 15th of May 1917 and was buried at Villers-Bretonneux France among 10,982 Australian graves, thirteen of which are known Aboriginal servicemen. As David Huggonson states, Villers-Bretonneux is a strange name for an Aboriginal burial ground, a strange resting grounds indeed, with their sons being buried at Beersheba, Israel; Menin Gate, Belgium; Heilly and Daours in France, it is no wonder the Walhallow families sought to have their sons remembered on Gamilaroi land and partake in the growing observance of ANZAC Day.

Walhallow’s William Archie Leslie, is memorialised at Villers-Bretonneux. It appears overseas memorials were not caught up in the ‘White Australia’ policies of the early twentieth century and memorialised all men. Unfortunately, William Archie Leslie is not commemorated on a local memorial in New South Wales, until the restoration of the Walhallow Roll of Honour in 2021.

The last that was known of Oliver White (Norman Briggs), he was in France. His family was notified of Norman being missing in October 1917, and for four agonising months, they waited until his status was updated to killed in action in February 1918. His father wrote to the A.I.F and informed them of his correct name and that he wished for it to be changed on his memorial inscription. He penned these words:

In a soldier’s grave, he is lying somewhere in France. Words can not tell the loss of the

ne we loved so well. Father and sisters Grace, Emily and Edward Briggs.

The inscription was never approved as it had 94 characters too many and the correction of his name was never amended. Today at the Menin Gate in Belgium, it reads Oliver White, aged 21 – Son of Edward and Elizabeth Briggs of Manilla.

Metres away another Briggs is mentioned, Frederick Briggs also from Manilla who died a month before Norman. On his enlistment papers, he put down that his dark skin was from his father’s Maori heritage, to sidestep the bias enlistment process. Frederick Briggs was awarded the Military Medal for distinguished bravery on the 23rd March 1917:

No. 16. Private Frederick John Briggs - On the night of February 24th/25th in a raid on the enemy’s trench, Private Briggs, while acting as covering bomber for the wire cutters, was severely wounded in the right arm, but with great grit and determination he continued bombing with his left hand. He thus prevented the enemy, who were in readiness at the point of entry, from inflicting further casualties on our wire-cutters, who were enabled to complete their work. His action contributed largely to the raiding party’s success in entering the trench.

Briggs was reported by a fellow serviceman on the 1st of October the same year as ‘shot in the head’ fatally, however, his body was never recovered. The two Brigg’s boys were both memorialised at the Manilla War Memorial in 1924, nominations for names to be included on the memorial were by public paid donations from their families.

Author Cate Hayton

- The full paper and references can be viewed here: https://historycouncilnsw.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Honourable-Mention-…

Australian War Memorial

Australian War Memorial